Watch short for this article (5 slides)

An Enigma at Sea: Understanding the Complex Orca Interactions with Vessels Off the Iberian Coast

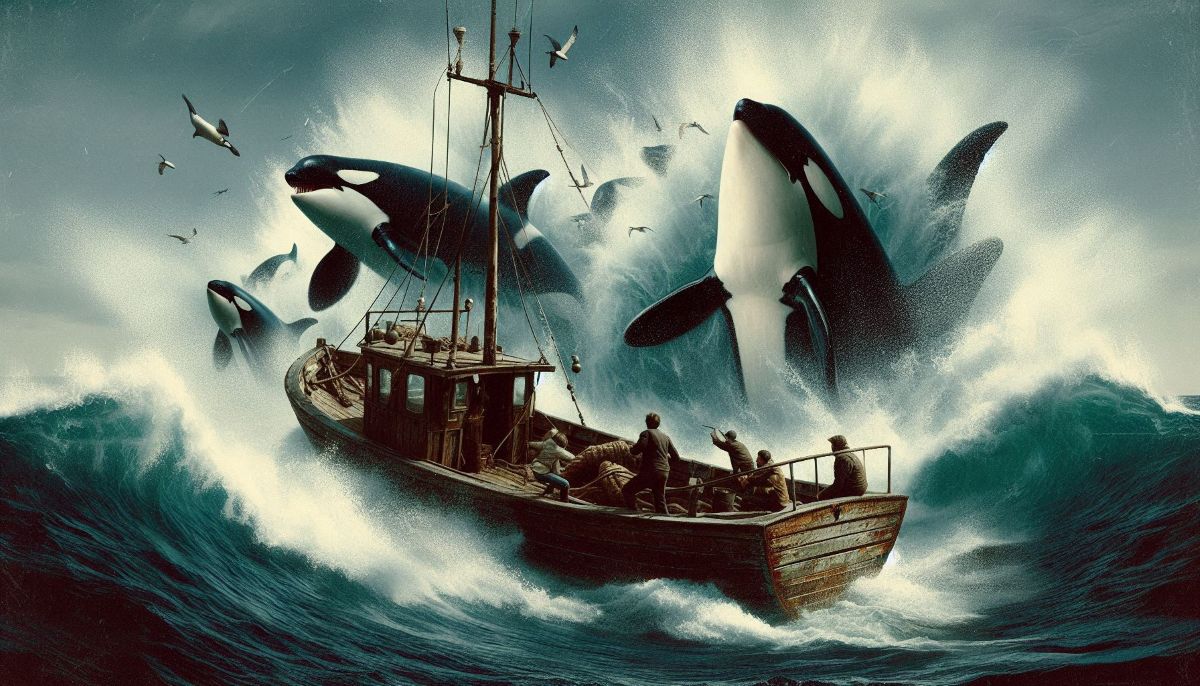

The waters around the Strait of Gibraltar have recently become the stage for a perplexing and concerning phenomenon: repeated, physical interactions between a specific group of Iberian orcas (Orcinus orca) and sailing vessels, primarily targeting their rudders. These encounters, sometimes escalating to the point of disabling or even sinking yachts, have captured global attention, sparking widespread speculation. Are these intelligent marine mammals engaging in deliberate "attacks," exhibiting a novel form of play, reacting defensively to perceived threats, or is something else driving this unusual behavior? While simplistic narratives of "revenge" are tempting, the reality is likely far more complex, rooted in the sophisticated intelligence, intricate social structures, and unique environmental pressures faced by this critically endangered orca subpopulation.

This article delves into the known facts surrounding these incidents, explores the leading scientific hypotheses, examines the remarkable cognitive abilities of orcas that allow for such behavioral innovations, and discusses the implications for both mariners and the conservation of these magnificent animals.

Giants of the Ocean Mind: Orca Intelligence and Social Learning

Often called "killer whales," orcas possess some of the largest and most complex brains on the planet, second only to sperm whales in absolute size and exhibiting a high degree of encephalization (brain size relative to body size). Their intelligence is not just theoretical; it's demonstrated through a remarkable array of behaviors:

- Complex Communication: Orca pods develop unique dialects of clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls, suggesting sophisticated communication systems used for coordination, social bonding, and navigation.

- Advanced Problem-Solving & Cooperative Hunting: Different orca populations (ecotypes) employ highly specialized and coordinated hunting strategies tailored to specific prey. Examples include creating waves to wash seals off ice floes (Antarctic orcas), temporarily beaching themselves to catch sea lions (Patagonian orcas), or using sophisticated teamwork to corral fish.

- Cultural Transmission: Behaviors, hunting techniques, vocal dialects, and even apparent "fads" are learned socially and passed down through generations within pods, primarily through matriarchal lines. This capacity for cultural learning is central to understanding how novel behaviors, like interacting with boat rudders, might spread.

- Tool Use (Potential): While debated, some observations, like Antarctic orcas using fish as bait for seabirds, hint at rudimentary tool use or complex manipulation of their environment.

- Self-Awareness & Complex Emotions: Studies suggest orcas exhibit self-awareness (e.g., recognizing themselves in mirrors) and possess brain structures associated with complex emotions and social cognition, similar to humans and great apes.

This high level of intelligence and reliance on social learning means orcas are capable of developing and propagating novel, sometimes surprising, behaviors in response to their environment or specific events.

The Iberian Orca Subpopulation: A Unique and Vulnerable Group

The orcas involved in the vessel interactions belong to a small, genetically distinct subpopulation inhabiting the waters around the Iberian Peninsula, primarily the Strait of Gibraltar and adjacent Atlantic areas. Understanding their specific context is crucial:

- Critically Endangered Status: This subpopulation is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List, with potentially fewer than 40 mature individuals remaining. They face numerous threats.

- Specialized Diet: Their primary prey is Atlantic Bluefin Tuna, particularly during the tuna's migration through the Strait of Gibraltar (spring and summer). This reliance makes them highly vulnerable to fluctuations in tuna populations and fishing activities.

- High-Traffic Environment: The Strait of Gibraltar is one of the world's busiest shipping lanes, experiencing intense traffic from large commercial vessels, ferries, fishing boats, and recreational yachts. This creates high levels of underwater noise pollution and constant potential for interaction.

- Fishing Pressure: They often interact with fisheries targeting bluefin tuna, sometimes learning to take tuna off longlines (depredation), which can lead to conflict and potential injury from fishing gear.

This specific ecological niche – a small, endangered population dependent on a specific prey item in a highly congested and noisy maritime corridor – forms the backdrop against which the boat interactions are occurring.

Decoding the Encounters: What is Actually Happening?

Since 2020, hundreds of interactions have been reported, documented largely by research groups like GTOA (Grupo de Trabajo Orca Atlántica). The behavior typically involves:

- Targeting Appendages: Orcas primarily focus on the boat's rudder and sometimes the keel.

- Physical Contact: They push, bump, bite, and ram the rudder, often causing significant damage (breaking rudders, damaging steering mechanisms).

- Persistence: Interactions can last from a few minutes to over an hour.

- Involvement of Specific Individuals/Groups: Research suggests a small number of individuals, particularly juveniles and subadults, are often involved, though adults are present. The behavior appears to be spreading within certain social units.

- Escalation: While initial interactions were less forceful, some have resulted in enough damage to render boats inoperable, requiring rescue, and at least three yachts have sunk following interactions as of early 2024.

It's crucial to note that despite the force involved and the damage to vessels, there have been **no reports of direct aggression towards humans** onboard during these events.

Exploring the "Why": Leading Scientific Hypotheses

While the exact motivation remains uncertain, researchers are investigating several plausible, potentially overlapping, hypotheses:

- Play Behavior / Behavioral Fad: This is currently considered a strong possibility by many researchers involved.

- Explanation: Orcas, especially juveniles, are naturally curious and playful. The rudder of a sailboat might offer unique sensory stimulation – perhaps the feel of the moving water deflected by it, the texture, or the sound it makes. An initial accidental or exploratory interaction by one or a few individuals might have been found intriguing and then copied by others through social learning, becoming a temporary "fad" within the group. Similar short-lived behavioral fads (like carrying dead salmon on their heads) have been observed in other orca populations.

- Supporting Points: The apparent focus on specific boat parts (rudders), the involvement of younger animals, and the lack of direct aggression towards people align with complex play behavior.

- Response to an Aversive Incident (Trauma Hypothesis): This theory suggests the behavior originated as a defensive response following a negative encounter.

- Explanation: It's hypothesized that one or more individuals, perhaps a key matriarch nicknamed "White Gladis" by some researchers, may have had a traumatic experience involving a vessel – possibly a collision, entanglement in fishing gear near a boat, or harassment. This could have triggered a defensive behavior directed at similar vessels, initially focused on stopping the perceived threat (e.g., breaking the rudder that controls movement). This behavior might then have been learned and replicated by other members of the pod, possibly perceived as a necessary defensive or precautionary action.

- Supporting Points: Could explain the sudden emergence and focus of the behavior. Defensive responses are well-documented in cetaceans.

- Stress, Resource Competition, or Displacement: The cumulative stress from the challenging environment could be a factor.

- Explanation: High levels of vessel noise, competition for declining tuna stocks (potentially with fisheries), and general habitat degradation could be stressing the orcas. The interactions might be a manifestation of this stress, perhaps a form of displaced aggression directed at vessels perceived as competitors or sources of disturbance.

- Supporting Points: The Iberian population is critically endangered and faces significant environmental pressures.

- Dismissing Anthropomorphic "Revenge": While emotionally resonant, attributing human concepts like deliberate "revenge" or coordinated "attacks" to punish humans is highly speculative and anthropomorphic. While orcas clearly learn from negative experiences and can exhibit defensive behaviors, framing it as intentional, malicious retribution lacks scientific evidence. The focus is on understanding the behavior as a learned response within their complex social and ecological context.

"While we can't definitively know the orcas' motivation, the patterns strongly suggest a behavior learned and transmitted socially within the group. Whether initiated by play, a negative experience, or environmental stress, it's now part of their behavioral repertoire in this region." - Synthesized perspective from GTOA research communications.

Implications and Safety Considerations

Regardless of the cause, the interactions pose risks:

- For Mariners: Significant vessel damage, loss of steering control, potential for sinking, need for rescue, psychological stress, and increased insurance costs or difficulty obtaining coverage in the region.

- For Orcas: Potential for injury from colliding with reinforced boat parts or propellers, stress from prolonged interactions, and the risk of negative human responses or harmful deterrent methods being employed.

Recommended Safety Protocols for Boaters

Based on observations and guidance from GTOA and maritime authorities, specific protocols are recommended if an interaction occurs:

- Stop the Boat: Discontinue sailing, take down sails.

- Disengage Autopilot & Engine: Leave the engine off (unless critically needed for immediate safety maneuver advised by rescue services). Let the wheel/tiller run free (avoiding sudden rudder movements that might further attract attention).

- Minimize Stimulation: Avoid shouting, making sudden movements, or trying to repel the orcas. Keep hands off the wheel/tiller. Stay away from the edges of the boat.

- Record and Report: Document the event (photos/videos if safe, GPS coordinates, time, duration, animal behavior, vessel details) and report it immediately to maritime authorities (e.g., Coast Guard) and relevant research groups (like GTOA via their app or website). This data is crucial for understanding the phenomenon.

- Check Navigation Charts/Alerts: Be aware of current areas designated as high-risk for interactions and consider avoiding them if possible, particularly during peak seasons. Some authorities may issue temporary navigation restrictions.

- Avoid Unproven Deterrents: The effectiveness and potential harm of acoustic deterrents or other methods are largely unknown and could potentially escalate the situation or harm the animals. Follow official guidance.

Conclusion: Coexistence Through Understanding

The ongoing interactions between Iberian orcas and vessels are a complex, evolving situation demanding careful study rather than sensationalism. Attributing human motives like "revenge" obscures the likely interplay of high intelligence, social learning, environmental pressures, and potentially specific initiating events. While play remains a strong hypothesis, the possibility of defensive learned behavior stemming from negative encounters cannot be dismissed. This phenomenon underscores the challenges of coexistence in increasingly crowded marine environments and highlights the need for continued research, adaptive management strategies (like temporary avoidance zones or speed advisories), and responsible boater behavior guided by scientific understanding. Respecting these critically endangered animals and minimizing negative interactions is crucial for both maritime safety and the future of this unique orca population.