Watch short for this article (5 slides)

Atlantis: Deconstructing the Legend of the Lost Civilization

The tale of Atlantis resonates through history as one of the most potent and enduring legends of a lost world. Introduced to Western thought by the Greek philosopher Plato over two millennia ago, the story depicts a magnificent island civilization – powerful, technologically advanced, and wealthy – situated beyond the "Pillars of Hercules" (commonly understood as the Strait of Gibraltar). Yet, according to the narrative, this utopian society succumbed to hubris and divine retribution, vanishing beneath the waves in a single, cataclysmic day and night. This evocative account has fueled centuries of fascination, inspiring countless expeditions, theories, and works of fiction. But was Atlantis a real place swallowed by the sea, or a sophisticated philosophical invention? Let's delve into Plato's original account, examine the persistent search for physical evidence, and explore the deeper meanings behind this captivating myth.

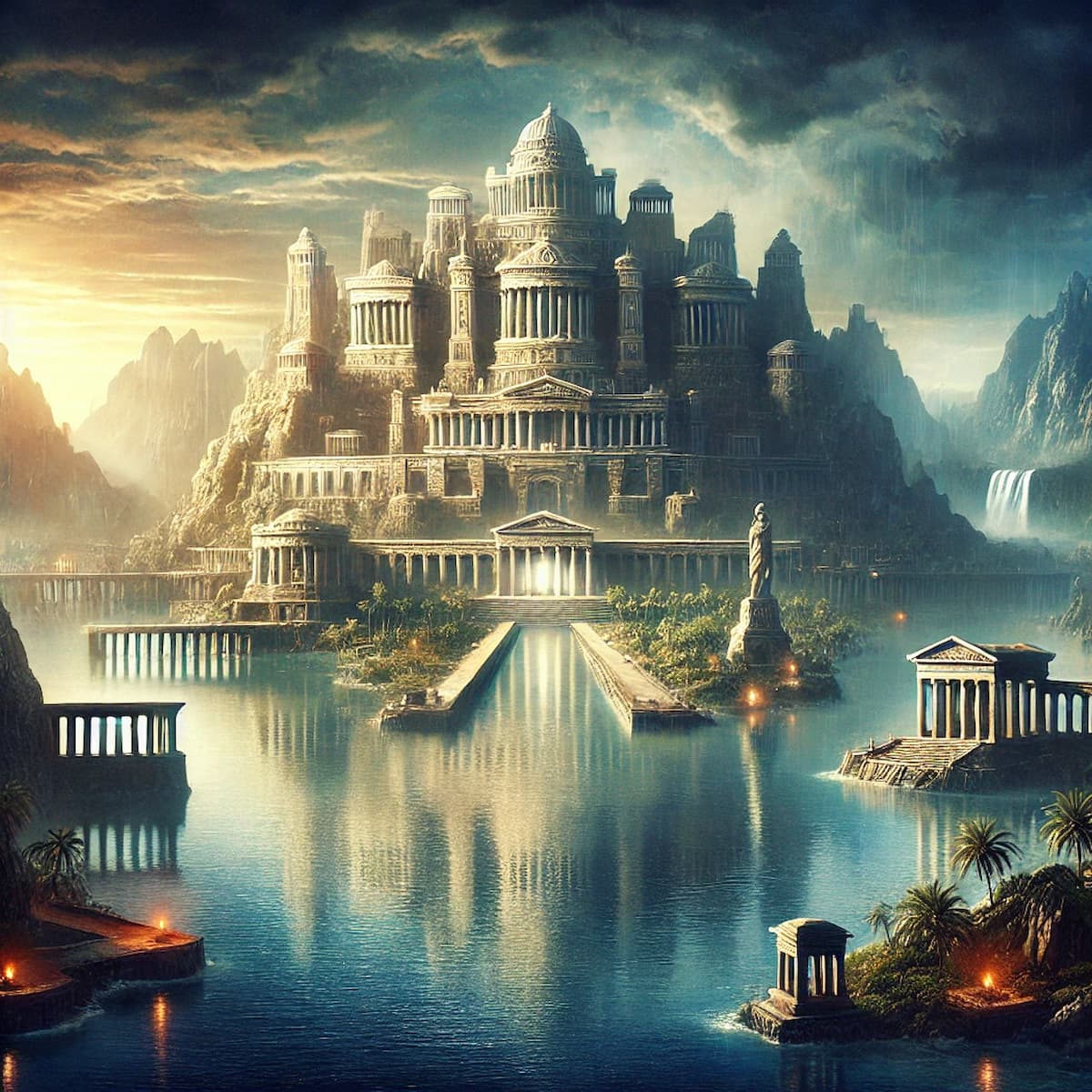

Photo by Mikhail Preobrazhenskiy on Unsplash - The idea of a lost, submerged civilization continues to fascinate.

Plato's Atlantis: The Foundational Narrative

Our sole primary source for the Atlantis story comes from two of Plato's dialogues, "Timaeus" and the unfinished "Critias," written around 360 BCE. It's crucial to understand these were philosophical works, not historical treatises.

- The Story's Framing: In the dialogues, the character Critias recounts a story passed down through his family, originating from the Athenian statesman Solon, who allegedly heard it from Egyptian priests. This framing immediately adds layers of hearsay and distance.

- Description of the Island: Plato describes Atlantis as an island larger than "Libya and Asia minor combined," located in the Atlantic Ocean beyond the Pillars of Hercules. Its capital city was a marvel of engineering: concentric rings of land alternating with circular canals, connected by bridges and tunnels.

- Resources and Society: The island was rich in natural resources, including abundant timber, diverse wildlife (even elephants), and precious metals like gold, silver, and the legendary, gleaming "orichalcum" (possibly a natural copper alloy like brass, or purely fictional). Atlantis possessed advanced agriculture supported by sophisticated irrigation, grand temples (notably one to Poseidon clad in silver and gold), palaces, harbors, and a powerful military comprising a large navy and army.

- Divine Origin and Political Structure: The Atlanteans were said to be descendants of Poseidon, the god of the sea, who divided the island among his ten sons, the first kings. This confederation of kings ruled justly for generations.

- The War and Downfall: According to Critias, some 9,000 years before Solon's time (placing it around 9600 BCE), Atlantis became corrupted by greed and ambition. It launched an imperialistic war against Athens and other Mediterranean peoples. Plato portrays an idealized, ancient Athens as the virtuous defender that heroically resisted the Atlantean invasion. Ultimately, due to their moral decay and hubris, the Atlanteans incurred divine wrath. In "a single dreadful day and night," catastrophic earthquakes and floods caused the island of Atlantis to sink beneath the sea, disappearing forever.

Plato's description is remarkably detailed, contributing significantly to the perception that it might be based on some historical reality.

Plato described Atlantis' capital as a sophisticated city of concentric rings and canals.

The Elusive Search: Evaluating Location Theories

Despite Plato's specific (though perhaps fantastical) details, centuries of searching have yielded no conclusive archaeological or geological proof of Atlantis as described. Numerous theories have emerged, often based on interpreting elements of Plato's story:

- The Minoan Civilization / Thera Eruption Hypothesis: This is perhaps the most academically discussed theory. It proposes that Plato's story was inspired by the Bronze Age Minoan civilization centered on Crete and the catastrophic volcanic eruption of Thera (modern Santorini) around 1600 BCE.

- Similarities: The Minoans were an advanced naval power with sophisticated art and architecture. The Thera eruption was one of the largest volcanic events in human history, burying the Minoan settlement of Akrotiri on Santorini in ash (similar to Pompeii) and generating tsunamis that likely devastated coastal Crete, possibly contributing to the decline of Minoan dominance.

- Discrepancies: Crucially, the timeframe is wrong (Minoans ~1600 BCE vs. Plato's ~9600 BCE), the location is wrong (Mediterranean vs. Atlantic "beyond the Pillars"), the size is vastly different, and Minoan Crete did not sink beneath the waves. While the Thera catastrophe might have contributed elements to a legendary tradition that reached Plato, it doesn't match his account directly. (Source: World History Encyclopedia - Minoan Civilization)

- Atlantic Locations (Azores, Canaries, Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Americas): Taking Plato's "beyond the Pillars" literally, some have searched the Atlantic.

- Challenges: Modern oceanography and plate tectonics render the idea of a large continent suddenly sinking in the mid-Atlantic geologically impossible. Oceanic crust is fundamentally different and denser than continental crust; large landmasses don't just disappear beneath the waves in this manner. Extensive seafloor mapping has revealed no evidence of such a sunken continent. (Source: NOAA Ocean Exploration - Plate Tectonics)

- Specific Claims (e.g., Bimini Road): Features like the "Bimini Road" in the Bahamas, sometimes cited as Atlantean remnants, have been conclusively identified by geologists as natural beachrock formations.

- Other Proposed Locations (Spain, Ireland, Antarctica, etc.): Numerous other locations have been proposed, often based on tenuous interpretations or fringe theories lacking credible scientific backing. Locations like Tartessos in southern Spain show evidence of an advanced Bronze Age culture that collapsed, but again, details don't align with Plato's Atlantis. Antarctica theories rely on unsupported ideas about ancient pole shifts or pre-ice civilizations.

- The Scientific Consensus: The overwhelming consensus among archaeologists, geologists, and historians is that Atlantis, as described by Plato, did not exist as a physical place. There is a complete lack of credible archaeological finds, geological evidence, or corroborating historical accounts.

Atlantis as Philosophy: Unpacking Plato's Allegory

Given the lack of physical evidence, most scholars interpret the Atlantis story within the context of Plato's philosophical aims.

- A Cautionary Tale: Atlantis serves as a powerful allegory about the dangers of hubris, materialism, imperialism, and moral decay. The initially virtuous society becomes corrupted by its wealth and power, leading to its divine punishment. This contrasts sharply with Plato's idealized depiction of ancient Athens, representing virtue, moderation, piety, and resilience.

- Political Commentary: Some scholars suggest Plato might have been subtly critiquing the Athens of his own time. Post-Peloponnesian War Athens had seen its own imperial ambitions lead to devastating consequences. The Atlantis story could serve as a warning against repeating those mistakes.

- Illustrating Ideal States: In "Timaeus" and "Critias," Plato uses both Atlantis and ancient Athens to explore concepts of the ideal state, justice, and the relationship between humanity and the divine – themes central to his major work, "The Republic." Atlantis represents a technologically advanced but morally flawed state, while ancient Athens embodies the virtuous, philosophical ideal (albeit a highly fictionalized version of Athens' past).

- Literary Device: Plato was a master storyteller. Atlantis provides a compelling narrative framework to explore complex philosophical ideas in an engaging way, characteristic of his dialogue form.

Viewing Atlantis as an allegory aligns perfectly with Plato's known methods and philosophical concerns, explaining the story's detailed nature without requiring a literal historical basis. (Source: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Plato)

The Enduring Power of the Myth: Why Atlantis Still Fascinates

Despite the lack of evidence and strong arguments for its allegorical nature, why does the Atlantis myth retain such a powerful grip on the popular imagination?

- Renaissance Revival: The rediscovery and translation of Plato's dialogues during the Renaissance reintroduced the story to European thought.

- Ignatius Donnelly's Influence: The publication of "Atlantis: The Antediluvian World" by Ignatius Donnelly in 1882 was pivotal. Donnelly disregarded the allegorical interpretation and argued passionately that Atlantis was a real, technologically advanced "mother culture" – the source of all ancient civilizations worldwide. His book, though based on pseudo-science, became immensely popular and heavily shaped modern perceptions of Atlantis as a literal lost continent with advanced technology.

- Modern Esotericism and Pseudo-Archaeology: Atlantis became a cornerstone for various esoteric traditions, New Age beliefs, and pseudo-archaeological theories, often linked to psychics like Edgar Cayce, pyramids, crystal power, or even ancient aliens.

- Psychological Appeal: The myth taps into deep human archetypes and desires:

- The allure of a lost "Golden Age" or paradise.

- Fascination with unsolved mysteries and the unknown.

- The tantalizing possibility of rediscovering advanced ancient knowledge or technology.

- The romantic notion of submerged cities and hidden worlds.

- Cultural Resonance: Atlantis has become a recurring motif in literature (Jules Verne, J.R.R. Tolkien's Númenor), film, television, comics, and video games, constantly reinforcing its presence in popular culture.

Conclusion: A Story for the Ages

The legend of Atlantis, born from the philosophical dialogues of Plato, remains one of history's most captivating enigmas. While the physical search for the lost island has yielded no credible evidence, leading scholars to conclude it was likely a sophisticated allegory, the story's power endures. Plato's Atlantis serves as a timeless cautionary tale about the corrupting influence of power and hubris, a vehicle for exploring ideal societies, and a reflection on the relationship between humanity, nature, and the divine.

Its persistence in popular culture, fueled by romanticism, pseudo-science, and our innate fascination with mystery, ensures that Atlantis continues to inspire imagination. Whether viewed as a philosophical construct or a tantalizing "what if," the story of the sunken civilization reminds us of the fragility of even the greatest societies and the enduring human quest to understand our past and uncover hidden truths, real or imagined.