Watch short for this article (5 slides)

The Unseen Bridge: Understanding Zoonotic Diseases and Protecting Ourselves in an Interconnected World

Zoonotic diseases, infections naturally transmissible from vertebrate animals to humans, represent a significant and growing global health challenge. Far from being rare occurrences, they are surprisingly common – estimates suggest that around 6 out of every 10 known infectious diseases in people can be spread from animals, and 3 out of every 4 new or emerging infectious diseases in people come from animals, according to the CDC. These illnesses can be caused by a variety of pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, parasites, and even prions. Understanding how these diseases spread, recognizing the risks associated with specific pathogens like the B virus recently highlighted in Hong Kong, identifying the factors driving their increase, and implementing robust prevention strategies are crucial for safeguarding public health.

What are Zoonotic Diseases? A Deeper Pathogen Dive

At its core, a zoonotic disease (or zoonosis) involves a pathogen successfully crossing the species barrier from an animal reservoir to a human host. The animal may or may not show signs of illness itself. The pathogens responsible fall into several categories:

- Viral Zoonoses: Caused by viruses. Examples include Rabies (often transmitted via saliva in bites from infected mammals like dogs, bats, raccoons), Ebola (linked to fruit bats and primates), Hantavirus (spread via inhalation of aerosolized virus from infected rodent urine/droppings), West Nile Virus (transmitted by infected mosquitoes), and B Virus (Macacine herpesvirus 1, primarily from macaques).

- Bacterial Zoonoses: Caused by bacteria. Examples include Lyme disease (transmitted by infected Ixodes ticks carrying Borrelia burgdorferi), Salmonellosis (often contracted from contaminated food products like poultry, eggs, or contact with reptiles), Anthrax (caused by Bacillus anthracis, spores can be inhaled or enter skin abrasions from infected animals/products), and Leptospirosis (spread through water contaminated with urine from infected animals).

- Fungal Zoonoses: Caused by fungi. Examples include Ringworm (dermatophytes transmitted by direct contact with infected animals like cats or dogs), Sporotrichosis (often contracted through skin punctures from plants contaminated with fungus carried by animals like cats), and Cryptococcosis (inhaled from environments contaminated with bird droppings, especially pigeons).

- Parasitic Zoonoses: Caused by parasites (protozoa, helminths). Examples include Toxoplasmosis (contracted from cat feces or undercooked meat containing Toxoplasma gondii cysts), Giardiasis (spread via contaminated water or food containing Giardia cysts shed by infected animals/humans), and Cysticercosis (infection with larval stages of the pork tapeworm, Taenia solium).

- Prion Zoonoses: Caused by abnormal protein particles (prions). The most cited example with a zoonotic link is Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), linked to consuming beef contaminated with the prion causing Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE or "Mad Cow Disease").

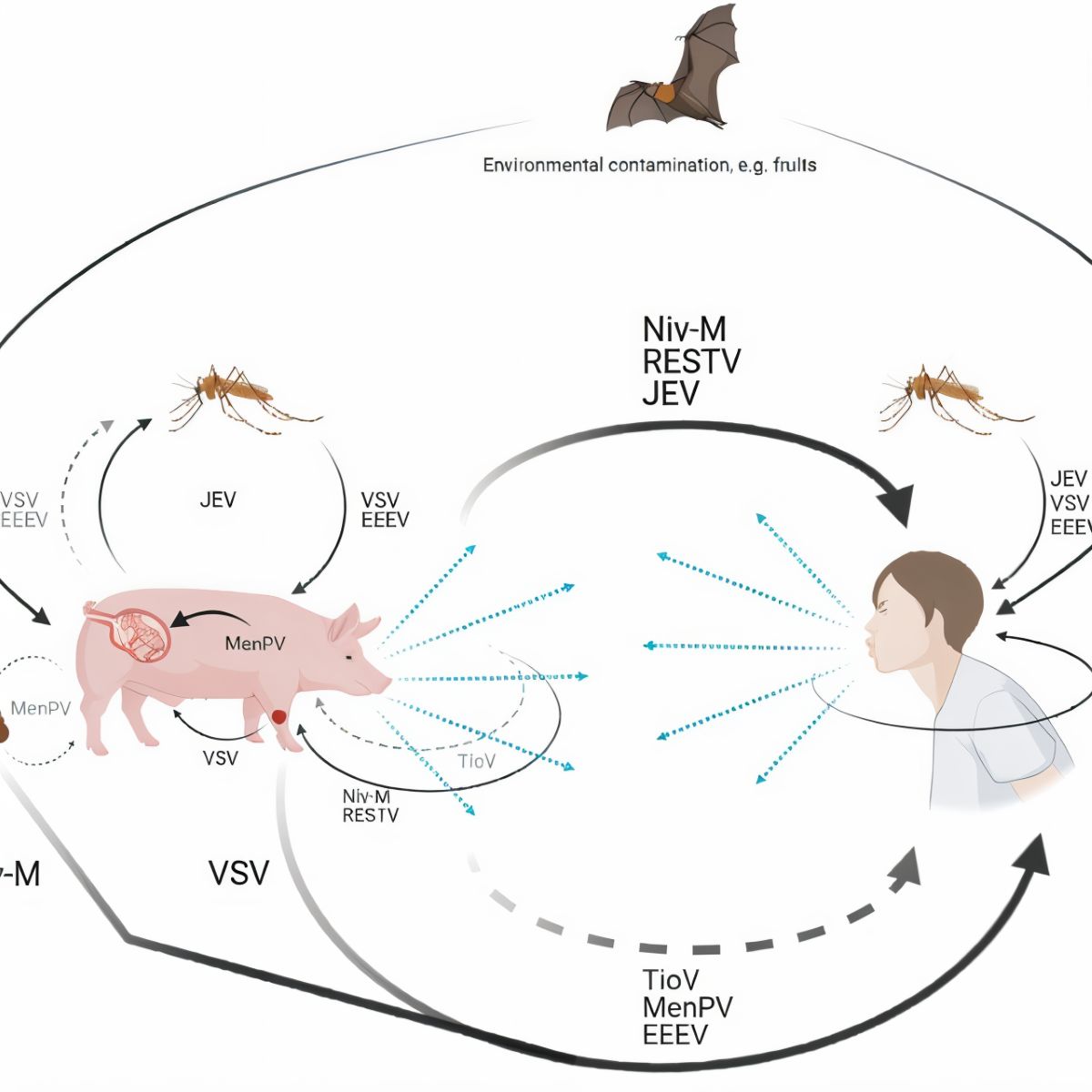

Complex Pathways: How Zoonoses Spread to Humans

Transmission routes are diverse and understanding them is key to effective prevention:

- Direct Contact: Touching, petting, handling, or being bitten or scratched by an infected animal. This also includes contact with infected bodily fluids like saliva, blood, urine, feces, or tissues.

- Examples: Rabies transmission through a bite; B virus via macaque bite, scratch, or splash of body fluids onto mucous membranes (eyes, nose, mouth); Ringworm from petting an infected cat.

- Prevention Focus: Avoid handling unfamiliar or wild animals. Use caution even with known animals. Crucially, wash hands thoroughly with soap and running water for at least 20 seconds immediately after contact with animals or their environments.

- Indirect Contact: Touching surfaces or objects (fomites) contaminated with pathogens from an infected animal. This includes animal habitats, soil, food/water bowls, or equipment.

- Example: Hantavirus contracted by sweeping up dust containing dried, aerosolized rodent droppings in an enclosed space.

- Prevention Focus: Regularly clean and disinfect animal living areas and objects they touch. When cleaning potentially contaminated areas (e.g., rodent infestations), wear gloves, potentially a respirator (like an N95), and wet down debris with disinfectant (e.g., a 1:10 bleach solution) before cleaning to prevent aerosolization.

- Vector-Borne: Being bitten by an infected arthropod, such as a tick, mosquito, flea, or fly, which has previously fed on an infected animal host.

- Examples: Lyme disease (ticks), West Nile Virus (mosquitoes), Plague (fleas).

- Prevention Focus: Use EPA-registered insect repellents containing ingredients like DEET, Picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus. Wear long sleeves and pants in vector habitats. Perform thorough tick checks after spending time outdoors. Control mosquito populations by eliminating standing water.

- Foodborne: Consuming food or water contaminated with pathogens from an infected animal. This is a very common route.

- Examples: *Salmonella* or *Campylobacter* from undercooked poultry or cross-contamination; *E. coli* O157:H7 from contaminated ground beef or produce; *Toxoplasma* from undercooked pork or lamb.

- Prevention Focus: Practice meticulous food safety: cook meats to safe internal temperatures (e.g., poultry to 165°F/74°C, ground meats to 160°F/71°C); wash fruits and vegetables thoroughly; avoid raw milk and unpasteurized juices; prevent cross-contamination by using separate cutting boards for raw meats and produce; wash hands before, during, and after food preparation. (CDC Food Safety Guidelines).

- Waterborne: Drinking or coming into contact with water contaminated by the feces or urine of infected animals.

- Example: Leptospirosis from swimming or wading in contaminated freshwater; Giardiasis from drinking untreated water.

- Prevention Focus: Avoid swallowing water from lakes, rivers, or pools. Treat water from natural sources before drinking (boiling, filtering, chemical treatment). Avoid contact with water potentially contaminated by animal urine, especially if you have cuts or abrasions.

- Airborne/Aerosol Transmission: Inhaling infectious droplets or dust particles containing pathogens.

- Examples: Hantavirus (aerosolized excreta); Q fever (inhaling dust contaminated by infected animal placentas, feces, urine); potentially Avian Influenza in close-contact settings.

- Prevention Focus: Use appropriate respiratory protection (e.g., N95 respirator) when working in high-risk environments (e.g., cleaning rodent-infested areas, working with livestock during birthing). Ensure adequate ventilation.

Spotlight on B Virus: A Rare but Serious Threat

The recent case involving B virus (Macacine herpesvirus 1) in Hong Kong underscores the potential severity of some zoonoses, even if human infections are rare.

- Natural Host: Macaque monkeys, where it typically causes mild or asymptomatic infections, similar to herpes simplex virus (cold sores) in humans.

- Transmission to Humans: Occurs primarily through bites or scratches from infected macaques. Exposure of broken skin or mucous membranes (eyes, nose, mouth) to macaque saliva, tissues, or fluids can also transmit the virus.

- Human Impact: While extremely rare in the general public, B virus infection in humans is a medical emergency. Without prompt antiviral treatment, it often leads to severe neurological disease (encephalomyelitis – inflammation of the brain and spinal cord) and has a high fatality rate, estimated at around 70-80% in untreated individuals. Symptoms can include fever, headache, muscle aches, fatigue, followed by neurological signs like pain/numbness near the exposure site, confusion, seizures, paralysis, and coma.

- Risk Groups: Individuals working closely with macaques (research laboratory personnel, veterinarians, zoo workers) are at highest risk. Tourists in areas with free-ranging macaques should exercise extreme caution and avoid feeding or touching the animals.

- Prevention & Response: Immediate and thorough wound cleansing (scrubbing the bite/scratch with soap, detergent, or iodine solution for a full 15 minutes, followed by running water for another 15-20 minutes) is critical. Prompt medical evaluation and consideration of post-exposure antiviral medication are essential. (CDC - B Virus Information).

Why the Rise? Drivers of Zoonotic Disease Emergence

The increasing frequency and impact of zoonotic disease outbreaks are not accidental. They are driven by complex, interconnected factors, many related to human activity:

- Habitat Encroachment and Land Use Change: Deforestation, agriculture expansion, and urbanization destroy natural habitats, reducing buffer zones between wildlife, livestock, and humans. This increases contact opportunities and stresses wildlife, potentially increasing pathogen shedding.

- Intensified Agriculture and Livestock Production: High densities of genetically similar animals can facilitate rapid pathogen spread and evolution. Close proximity between livestock, wildlife, and humans creates spillover opportunities.

- Wildlife Trade and Markets (Legal and Illegal): Bringing diverse species from different regions into close, often unsanitary, contact under stressful conditions creates a perfect storm for pathogen exchange and amplification.

- Climate Change: Altered temperature and rainfall patterns shift the geographic ranges of animal reservoirs and vectors (like mosquitoes and ticks), exposing new populations to diseases. Climate-related disasters can also displace animals and humans, increasing contact.

- Globalization, Travel, and Trade: The rapid movement of people, animals, and goods across the globe allows pathogens to spread quickly from a localized outbreak to an international crisis.

These factors highlight the importance of the "One Health" approach, recognizing that the health of people, domestic animals, wildlife, and the environment are inextricably linked. Addressing zoonotic threats requires collaboration across human medicine, veterinary medicine, and environmental science sectors. (WHO - Zoonoses Fact Sheet).

"The health of humans, animals and ecosystems are interdependent. Changes in the environment, like deforestation or climate fluctuations, can disrupt this balance, increasing the risk of diseases passing from animals to humans." - Paraphrased concept from the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, founded as OIE).

Protecting Ourselves: Actionable Prevention Strategies

While eliminating zoonotic risk entirely is impossible, numerous effective measures can significantly reduce exposure and transmission:

| Prevention Category | Specific Actions & Details |

|---|---|

| Hand Hygiene | Wash hands thoroughly with soap and running water for at least 20 seconds: after touching animals/pets, their food, waste, or habitats; before eating or preparing food; after being outdoors; after removing gloves. Use alcohol-based sanitizer (>60% alcohol) if soap/water unavailable. |

| Avoid Risky Animal Contact | Do not touch, feed, or handle wild animals, especially those appearing sick or unusually tame. Avoid contact with rodents and their droppings. Supervise children closely around animals. Do not encourage wild animals near your home. Exercise extreme caution around unfamiliar domestic animals. Never approach or handle bats. |

| Vector Control | Use EPA-registered insect repellent (DEET, Picaridin). Wear protective clothing in tick/mosquito areas. Check yourself, children, and pets for ticks daily after outdoor activity; remove ticks promptly and correctly. Eliminate standing water sources where mosquitoes breed. |

| Food Safety Practices | Cook meats to safe internal temperatures. Wash produce thoroughly. Avoid unpasteurized dairy/juices. Prevent cross-contamination (separate cutting boards, utensils for raw meat/produce). Refrigerate leftovers promptly. |

| Pet Health & Hygiene | Ensure regular veterinary care, including vaccinations and parasite prevention. Clean pet food/water bowls daily. Dispose of pet waste properly. Wash hands after handling pets, especially reptiles and amphibians (high *Salmonella* risk). Prevent pets from hunting or interacting with wildlife. |

| Wound Care | Immediately and thoroughly clean any animal bite or scratch wound with soap and running water for at least 5-15 minutes (longer for potential B virus exposure). Seek prompt medical attention, report the incident as required, and discuss tetanus/rabies prophylaxis. |

| Protective Measures in High-Risk Settings | Individuals in high-risk occupations (vets, farmers, lab workers, wildlife biologists) should use appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) like gloves, masks/respirators, eye protection, and follow strict biosecurity protocols. |

Recognizing Symptoms and Seeking Help

Symptoms of zoonotic diseases vary widely depending on the pathogen. Common initial signs often include non-specific flu-like symptoms: fever, headache, muscle aches, fatigue, and sometimes gastrointestinal issues. However, some diseases have characteristic signs (e.g., the bullseye rash of Lyme disease, neurological deterioration in Rabies or B virus infection). If you develop unusual symptoms after potential exposure to animals, vectors, or contaminated environments, seek medical attention promptly. Crucially, inform your healthcare provider about any recent animal contact, tick/mosquito bites, travel history, or consumption of potentially risky foods.

Conclusion: A Shared Responsibility in Our Interconnected World

Zoonotic diseases are an inherent part of our shared planet, linking human health directly to the health of animals and the environment. Factors like habitat disruption, climate change, and globalization are increasing the frequency and potential impact of these cross-species infections. While the threat is real, knowledge and proactive prevention are powerful tools. By practicing diligent hygiene, ensuring food safety, controlling vectors, handling animals responsibly (both domestic and wild), and supporting "One Health" initiatives that promote integrated surveillance and response, we can significantly reduce our risk and build a healthier future for all species.